January 2, 2015Comments are closed.cats

Let’s say your city has a ‘cat problem’. These guys live alongside humans, eating our garbage, vermin and generally doing what cats do. Some of these cats will be pets. The majority will be unowned, free roaming and stray cats – that is, no one person has taken ownership.

Despite claims cats can reproduce ‘exponentially’, this simply isn’t true. The number of cats who can live in any environment is regulated by that environment; if this weren’t true, with the rate that cats are purported to breed, we’d all be walking waist deep in cats every day. There is a naturally maintained population limit – a cat population will hit its maximum, and unless something significant happens, stay pretty much constant. Survival of the fittest and all that.

In our example (and for ease of calculations) our city can maintain a population of…

So what are our options for managing these cats?

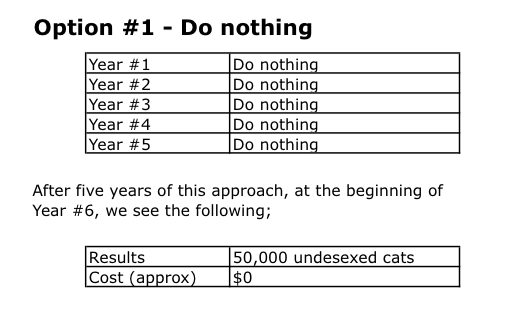

Surprisingly, doing nothing is actually the option that many cities choose. Put cats in the ‘too hard’ basket and do nothing at all about them. A few get picked up by cat charities. A few get adopted off the street. And most just live a free-roaming life supported by humans in varying degrees. It is executed like this;

As no impact was made on the breeding capacity of the base cat population, the overall cat population has remained unaffected. But the approach also didn’t cost a penny, so no harm done.

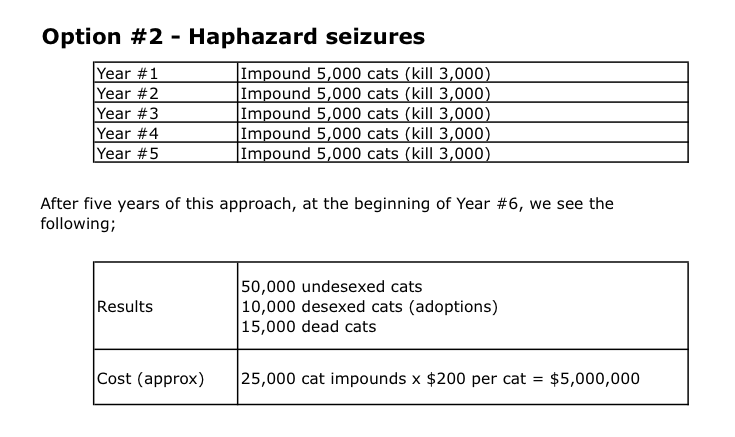

Haphazard seizures is how most cities manage their cat populations. A fraction of the overall cat population is taken into shelters every year (less than 10%). This percentage is not enough to make a dent in the breeding population, meaning this work is largely futile. Strays brought in by the public, targeting ‘hoarders’, trapping and lending traps – none effect the cat population in any meaningful way.

It is an expensive approach, as seizing, holding and rehoming or killing a cat is extremely labour intensive (it is estimated each cat processed in this way will cost a city more than $200). It is also a massively inhumane approach, as cats tend to get stressed and sick in the shelter environment. Only 2% of cats in Australia are reclaimed as owned, meaning 98% or so will need to be rehomed or destroyed.

As no impact was made on the breeding capacity of the base cat population (not enough cats were removed in any one year), the overall cat population has remained unaffected.

But the true tragedy of the approach is that more than $5 million over 5 years was wasted on it! In animal welfare there is never enough money to go around, and spending multiple millions on killing cats is a massive waste of resources.

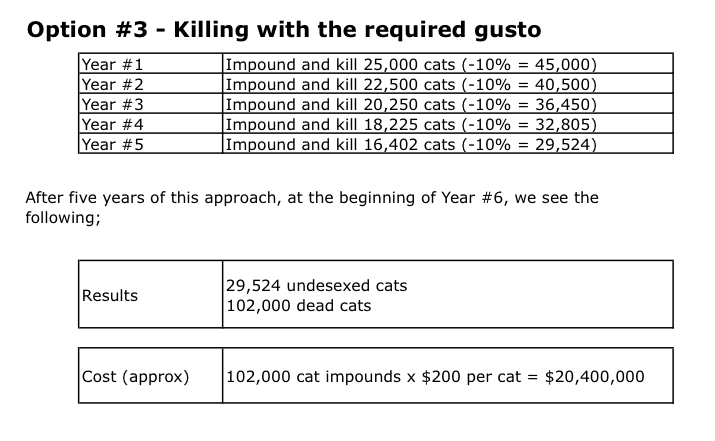

In 2004 Andersen, Martin and Roemer used computer population modelling* to predict the required percentages needed to manage cat populations. While not an exact science, it does give us some idea of how much killing would need to take place to reasonably speculate a ‘managed’ cat population.

The model predicted the cat population could be controlled by the annual culling of >50% of the total cat population. This was predicted to result in a cat population that declined by approximately 10% per year.

Killing with the required gusto takes some serious investment. Killing more than 100,000 cats in a single community – in just five years – takes a real disregard for community compassion towards these animals. Not to mention a shelter willing to provide a team of cat killers with zero qualms about acting as cat-abattoir workers. It’s unlikely to be a popular approach. Most people are likely to balk when presented with the reality of such a large amount of tax-payer funded killing.

Not to mention the $20 million dollar investment. Yes, you read that right, $20 million dollars. Assuming this killing was done at a shelter (widespread hunting, baiting or shooting would be unlikely to be approved for urban use), shelters would need to given a lot of financial support. Finding $20 million dollars in five years to kill cats, will not be easy. Especially considering at the end of the five years, you’re not even half way to killing the prescribed number of animals.

(Proposing that these cats could be killed by less hands-on means; shooting or baiting for example, is unrealistic – if you’re going to take 100,000 cats out of the community and kill them, then you had better have checked and double checked you’re not killing anyone’s pets.)

How long will this approach take? Well, it can be expected according that at least a twenty year investment of solid killing would be needed to conceivably reduce cat numbers to a few thousand. With one disclaimer. New cats from other areas can and will move into any area now vacant of cats. Could any level of killing see cats driven out of a city? It’s hard to see how.

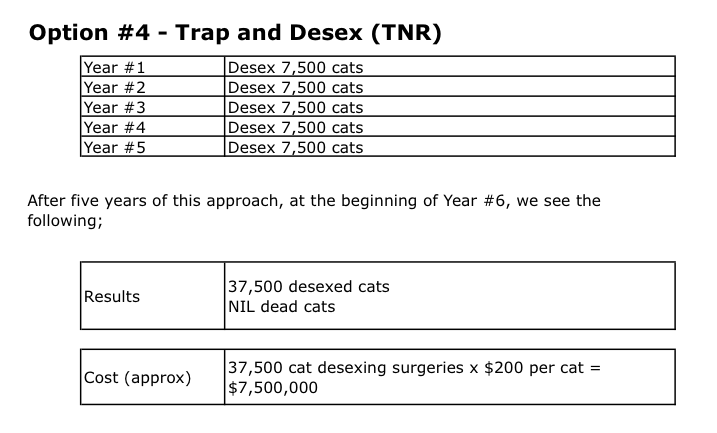

Based on the same modelling on cat populations used above, the researchers endeavoured to forecast the results of TNR. The results suggest that… “in excess of 75% of the fertile population would need to be maintained, on an ongoing basis, to cause a population decrease in a TNR program”… and… “TNR programs are not likely to convert increasing cat populations into declining populations or even stable populations until the (desexing) rate is quite high.”

Now, the cat population is already managed primarily by the load-carrying capacity of the environment, so there is no reason to believe that in Australia after 200 years or so, that this cat population isn’t already stable. What a successful cat management program would obviously be trying to do then, is reduce this population. So we could do, thus;

Now of course $7.5 million dollars is a lot of money, especially over just five years. But it’s basically a third of the cost of killing cats ($20 million) to obtain a less effective result, and at the end of it there isn’t 100k dead cats to deal with. It’s also only slightly more than what is being spent already supporting haphazard seizures ($5 million) but it is likely to be a reducing cost over time.

There is no reason why this has to be rolled out over 5 years, except for our comparison. Every desexed cat is a step in the right direction. The cats can be owned or unowned – it really doesn’t matter. Offering people free desexing for their cats is likely to be extremely popular; much, much more popular that accidentally killing their pets in a massive cull.

In addition, most communities are not trying to manage anywhere near 50,000 cats, meaning it may take a fraction of this to get the job done.

It is often asked – does TNR work?

That is the wrong question. The question needs to be, what are we measuring, what is our measure of success and how do we achieve it?

If we’re measuring based on effectiveness, what we’re doing now – mostly nothing and haphazard seizures – then what we’re doing now definitely isn’t working. Doing nothing is free, but most people would agree it is insufficient and that we could do so much better. Haphazard seizures have allowed charity pounds to grow enormously bloated and wealthy, but after decades of offering cat-killing services to local councils, anyone who cares about cats would surely want better for their welfare.

Leaving us with two equally viable options for an effective approach. We can begin killing with the required gusto, we can work to expand the killing to 50% of the total cat population and condemn millions and millions of cats to suffering impounded in a shelter, then ask shelter staff to hold each of these cats down and inject them with poison. We can redesign shelters and pounds to be industrial cat-killing facilities, even more callous and abhorrent than the highest kill shelter that exists today… or we can use TNR and protect cats. All cats, regardless of ownership status. We can offer them the chance to continue to live their lives, help them if they need it, and desex and release all cats who can’t be housepets.

But, maybe we’re not measuring effectiveness – maybe we’re simply measuring cost. TNR could be executed on 75% of a 50,000 strong cat population for around $7.5 million dollars. To kill the required number of cats, would cost $20 million.

Does TNR work? Well, it’s more effective than what we’re doing now, it costs much less than killing, and it saves the lives of animals. By every measure it is the best imperfect solution, where a perfect solution does not exist.

*Reference: Use of matrix population models to estimate the efficacy of euthanasia versus trap-neuter-return for management of free-roaming cats – Mark C. Andersen, PhD; Brent J. Martin, DVM, DACLAM; Gary W. Roemer, PhD JAVMA, Vol 225, No. 12, December 15, 2004

It would be so great to implement the “Trap, Spay/ Neuter and Return Program” – like in many European countries and other more advanced countries in the world. This is the right solution to reduce the number of strays or feral cats born every year and stop killing so many. I cannot understand why it’s so difficult for local Councils to implement new and more effective animal welfare laws to educate people to treat animals with respect, care for them and help their citizens to desex their cats and dogs with lower fees. Councils should also use the TNR strategy for the strays. The TNR has been used already successfully in Europe and other more advanced countries in the world and the number of unwanted or neglected cats in the areas has decreased dramatically. Please help all those cats and kittens who are born to die in shelters every year. Cats deserve better!

Fabulous article and analysis with excellent reasoning and conclusions! I see it was written in 2004 and it’s now 2015, so unfortunately, even more than a decade later nothing has changed to adopt this so obviously better approach! My immediate thought is not to give up but to just be more assertive with these facts, educate people and Councils, this is a great article to send them! I’m definitely saving it as my precious point of reference. All animals activists should use this article as their main “weapon”! Thanks, authors if this work – keep up the good work!